Deep learning-driven conversion of scanning superlens microscopy to high depth-of-field SEM-like imaging

Description of microsphere-based SSUM utilizing deep learning

In microsphere-based SSUM, the diameter of microspheres determines their focal length, directly influencing the system’s magnification. Smaller microspheres yield higher magnification and more detailed imaging, though this enhancement is fundamentally constrained by the diffraction limit. Differences in refractive indices between microspheres and the surrounding medium can cause image aberrations, significantly affecting resolution, especially when these differences are substantial. Therefore, when optimizing the design of super-resolution imaging systems, it is crucial to consider these factors comprehensively. By understanding and carefully manipulating these parameters, researchers can effectively enhance the performance of microsphere-based SSUM.

The well-known Rayleigh criterion unequivocally indicates that resolution is fundamentally constrained by both wavelength and numerical aperture26, and these limits are insurmountable. Conventional methods to enhance microscope resolution typically involve employing light sources with shorter wavelengths, increasing numerical aperture, utilizing media with refractive indices matched to the system, and correcting optical system aberrations. Hence, microspheres with higher refractive indices have been used to improve image quality beyond the diffraction limit. For example, when a microsphere comes in contact with a specimen, the solid-immersion concept is employed to approximate the resolution of diffraction-limited imaging based on microspheres, yielding approximately λ ⁄(2 ns), where ns represents the refractive index of the microsphere27,28. For instance, when ns equals 1.9 (as observed in barium titanate glass microspheres), λ ⁄(2 ns) equals λ/3.8. Consequently, optical super-resolution based on microspheres is defined as a resolution surpassing λ/3.8. Nevertheless, the physical factors and conditions present formidable challenges, hampering significant strides in imaging resolution. Additionally, factors such as microsphere diameter, non-uniform incident light distribution, and discrepancies in focusing markedly influence the eventual image quality. For example, the diameter of microspheres affects their focal length, which in turn influences the overall magnification of the system. Decreasing the microsphere diameter increases the magnification, allowing for more detailed imaging. Moreover, refractive index differences between the microsphere and the surrounding medium can introduce aberrations in the images formed by the spherical lens. These aberrations can significantly impact resolution, particularly when there is a substantial difference in refractive indices. Therefore, when optimizing the design of super-resolution imaging systems, it is crucial to consider several factors comprehensively. By understanding and carefully manipulating these parameters, researchers can effectively enhance the performance of microsphere-based SSUM.

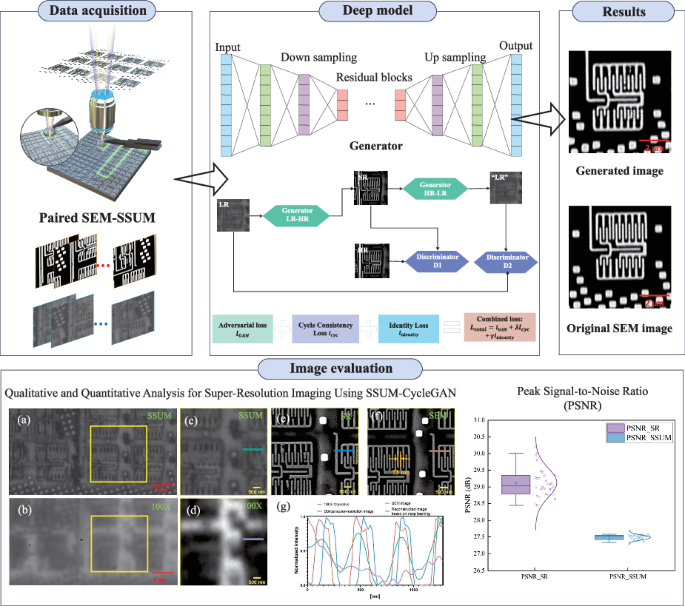

In this work, deep learning methods are used to transform microsphere-based super-resolution images into SEM large depth-of-field images. Deep learning leverages the inherently powerful fitting capability of neural networks and advanced feature learning techniques to generate high-resolution images based on lower-resolution inputs. By training Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), this approach comprehensively interprets complex image features, thus recovering finer details from blurry and low-resolution images, as shown in Eq. 1.

$$\mathop\limits_\mathop\limits_V\left(D,G\right)=_{^ \sim _\left(^{}\right)}\left[{\text}D\left({I}^{{HR}}\right)\right]+{{\mathbb{E}}}_{{I}^{{LR}} \sim {P}_{{data}}\left({I}^{{LR}}\right)}\left[{\text{log}}\left(1-D\left(G\left({I}^{{LR}}\right)\right)\right)\right]$$

(1)

The entire formulation consists of two components. IHR represents the SEM super-resolution image, and ILR represents the optical super-resolution image input to the G network. Also, G(ILR) represents the SEM super-resolution image generated by the G network, and D(IHR) represents the probability assigned by the D network to ascertain the authenticity of the SEM image (since IHR is a genuine SEM image, for D, the closer this value is to 1, the better). On the other hand, D(G(ILR)) is the probability assigned by the D network to determine whether the image generated by G is an authentic SEM image. Therefore, during the training process, to enhance the generation capability of the generator G and the discrimination capability of the discriminator D, the objective is to find the minimum value for G and the maximum value for D.

To transform optical super-resolution images into SEM images, CycleGAN is built upon the GAN model to effectively address the domain adaptation challenges between two distinct image domains, as illustrated in Eq. 2 below.

$${l}_{{cyc}}\left({G}_{{LR}-{HR}},{G}_{{HR}-{LR}},{I}^{{LR}},{I}^{{HR}}\right)={{\mathbb{E}}}_{{I}^{{LR}} \sim {P}_{{data}}\left({I}^{{LR}}\right)}\left[{{||}{G}_{{HR}-{LR}}\left({G}_{{LR}-{HR}}\left({I}^{{LR}}\right)\right)-{I}^{{LR}}{||}}_{1}\right]+{{\mathbb{E}}}_{{I}^{{HR}} \sim {P}_{{data}}({I}^{{HR}})}\left[{{||}{G}_{{LR}-{HR}}\left({G}_{{HR}-{LR}}\left({I}^{{HR}}\right)\right)-{I}^{{HR}}{||}}_{1}\right]$$

(2)

Here, GLR-HR and GHR-LR respectively represent the processes of mapping optical super-resolution images ILR to SEM images IHR and the reverse transformation. In general, optical microscopy images and SEM images typically exhibit distinct appearances, textures, and resolutions, and the relationship between them may be complex and nonlinear. CycleGAN is designed to handle non-paired data, meaning there is no direct correspondence between the two domains. This allows the model to learn to map images from one domain to another, even in the absence of paired training data. Overall, CycleGAN provides an effective framework for learning complex mappings between optical microscopy and SEM images on paired datasets, enabling cross-domain image transformation. Thus, deep learning-based super-resolution imaging techniques using CycleGAN not only address the limitations of traditional optical microscopes in resolving details smaller than half the wavelength due to optical diffraction but also overcome the challenges encountered by microsphere-based super-resolution imaging systems. These challenges arise from factors such as microsphere diameter and light source wavelength, fundamentally limiting imaging resolution.

Principle and design of the optical super-resolution system

Based on our previous work11,29, a non-invasive, high-throughput, environmentally compatible optical SSUM system was developed, and the composition and performance characteristics of the systems are shown in the Supplementary. Figure S1 shows the photograph of the physical configuration of the SSUM, which can be used for large-area, super-resolution imaging and data acquisition. The optical super-resolution imaging system consists of an AFM, a commercially available cantilever (TESP probe, Bruker), a 57-μm-diameter BTG microsphere lens (Cospheric), and a 50× objective lens (Nikon LU Plan EPI ELWD). Microspheres are attached to the AFM probe cantilever using a UV-curable adhesive (NOA63, Edmund Optics). Different illumination conditions are achieved by adjusting two stops in the Köhler illumination system (Thorlabs). A high-speed scientific complementary metal oxide semiconductor camera (PCO.Edge 5.5) is used to record the images. Illumination is provided by an intensity-controlled light source (C-HGFI, Nikon, Japan), with the peak illumination wavelength of the system set to ~550 nm for white light imaging by the optical elements. A drop of UV-cured adhesive is positioned close to the microsphere region to act as the sticky material. The selected microspheres are touched by the adhesive-coated tip, which is then subjected to UV light for 90 s until the adhesive is fully cured. The microsphere superlens is mounted to the AFM cantilever and kept in place during scanning to keep the distance between the microsphere and the objective as consistent as possible. The specimen is placed on top of the stage after the standard AFM adjustments are completed. The scanning platform and 3D translation stage are used to carry out horizontal sample scanning and vertical focus adjustment. The IC chip scanning in the horizontal direction and the feedback adjustment in the longitudinal direction are realized by a 3D piezoelectric ceramic (PZT) scanner (P-733.3CL, Physik Instrumente, Germany), in the process of which the AFM feedback is acquired to monitor whether the microspheres are touching the sample surface and to adjust the distance between the microspheres and the sample. When the distance or force reaches a certain value, the optical microscope is driven by a translation stage with nanoscale resolution (IMS100V, Newport) to capture a virtual image generated by the microsphere. The interval of the IC chip scan and the interval of the signal used to trigger the camera image recording are both adjusted according to the region of the field of view of the microsphere superlens during horizontal scanning. Before scanning, the camera’s captured area can be modified to satisfy the overlapping requirement for image stitching, and there is no considerable aberration in the field of view of the microsphere superlens, which effectively reduces data processing time and allows for fast image processing before or after scanning.

SEM image acquisition

The HR images are captured using a QuantaTM 450 FEG-SEM (field-emission gun scanning electron microscope; SEI) with a beam voltage of 30 KeV and a spot size of 4.0.

Image pre-processing

To enable the model to better learn the mapping relationship between SSUM images and SEM images, image processing of the captured SSUM images and SEM images is necessary. To gather the SSUM (low-resolution) and SEM (high-resolution) image pairs of the same samples for network training, it is first necessary to stitch together each frame image taken by the SSUM to obtain an optical super-resolution image of the wafer. After that, the SSUM image is registered with the SEM image, matching the fields of view of the LR and HR images so that each training pair shows roughly the same region of the sample, and cropping them to 512 × 512 pixels. If the effective pixel sizes of the LR and HR images differ (e.g., due to being captured with different devices such as the SSUM system and SEM), they are rescaled to the same physical size. The cropped image pairs are then sorted into two groups for use as training and test datasets, with the training dataset being fed into the neural network for model training. In terms of network structure design and loss function, a network model is built by combining convolutional neural networks and multiple residual blocks, and the loss function is designed based on prior knowledge; model training is then performed to determine the optimizer and learning parameters, and the network parameters are updated using a backpropagation algorithm to improve the model’s learning ability by minimizing the loss function. The network model is evaluated according to the performance of the trained model on the validation set, and corresponding adjustments are made. Finally, the trained generative model is tested with the test dataset images to evaluate the tested image quality (see Supplementary Fig. S2).

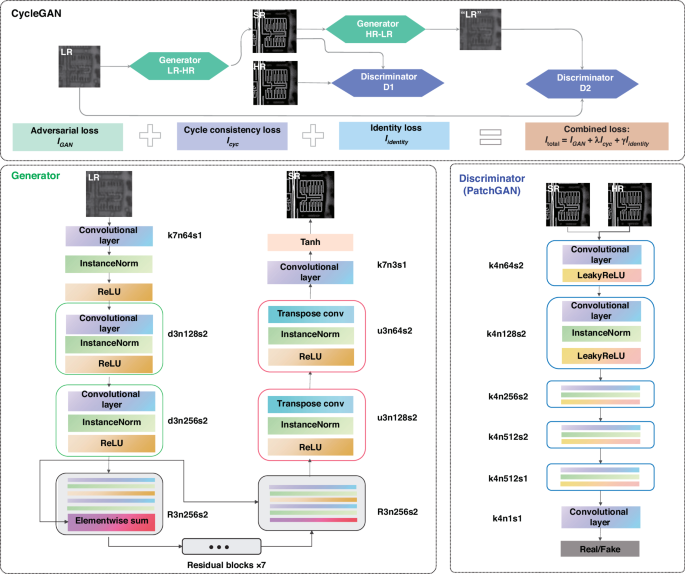

Design of CycleGAN with multi-residual block network architecture

CycleGAN is a method for training deep convolutional neural networks for image-to-image translation tasks, with the network structure and loss function shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. The basic goal of this translation is to use a network to learn a mapping between input and output images. During the training phase, cycle consistency is needed: that is, one image identical to the original should be produced with the lowest L1 loss value following repeated application of two different generators. Supplementary Fig. S4 shows the variation in loss for the generator and discriminator in the image super-resolution model, after numerous iterations.

Network architecture

The network structure of the CycleGAN with multi-residual blocks is shown in Fig. 7. Its main principle is to train the generator and discriminator models to convert images from low to high resolution with cyclic consistency, such that the generated super-resolution image should subsequently be back-converted to the LR image. The generator is designed to learn how to transform features of SSUM images into features resembling those of real images, while the discriminator is trained to differentiate between real and synthetic images. For the discriminator networks, 70 × 70 PatchGANs are utilized, which focus on classifying each patch in the image as real or fake. A patch-level discriminator architecture has fewer parameters than a full image discriminator and can be applied to arbitrarily sized images in a fully convolutional fashion. For each training batch, the generator and the discriminator compete against each other so that the generator learns to produce features sufficiently similar to the real image to fool the discriminator, bringing the generated super-resolution images closer to the real high-resolution images.

Structure of image super-resolution network based on CycleGAN with multi-residual blocks

Generator architecture

The generator comprises three primary modules: the downsampling module, the residual module, and the upsampling module. In the training process, the SSUM image is initially downsampled to an LR image. Subsequently, the generator architecture attempts to upsample the LR image to achieve super-resolution, and shallow features are extracted using convolution. The residual blocks are then used to extract the deeper features. The generator architecture then attempts to upsample the image from low resolution to super-resolution using the upsampling module. After this, the image is passed into the discriminator, which tries to distinguish between the SEM image and the generated super-resolution image and generates the adversarial loss for backpropagation into the generator architecture.

In the network structure diagram in Fig. 7, k, d, R, and u represent the convolution kernel size of the convolution layer, downsampling layer, residual block, and upsampling layer, respectively. To extract residual characteristics from both LR and HR images, a deep learning network structure is built with nine residual blocks for 256 × 256 resolution training images. The generator architecture contains residual networks instead of deep convolutional networks because residual networks are easier to train and can thus be substantially deeper to generate better results. The benefit arises from the residual network using a type of connection called skip connections. There are nine residual blocks, generated by ResNet. Within each residual block, two convolutional layers are used with small 3 × 3 kernels and 64 feature maps, followed by batch normalization layers and LeakyReLU as the activation function. The resolution of the input image is increased using two trained sub-pixel convolution layers. The above-mentioned network structure can adaptively learn the parameters of the rectifier and improve the accuracy at negligible extra computational cost.

Discriminator architecture

The task of the discriminator is to discriminate between real HR images and generated super-resolution images. The discriminator architecture used in this paper is a 70×70 PatchGAN architecture with LeakyReLU as the activation function. The structure also uses instance normalization. The network contains five convolutional layers. With the deepening of the network layers, the number of features increases, and the feature size decreases. The first four layers have 4×4 filter kernels, increasing by a factor of 2 from 64 to 512 kernels with stride 2, which is the convolutional-InstanceNorm-LeakyReLU structure. The last layers of the discriminator use filter kernels of size 512 with stride 1.

Datasets

The registered SSUM images and SEM images are input into the neural network as LR/HR image pairs and cropped to 512 × 512 pixels. To improve training efficiency, the input image size is resized to 256 × 256 pixels. The training set has 704 image pairs. All the network output images shown in this paper were blindly generated by the deep network; that is, the input images had not previously been seen by the network. However, if such training image pairs are not available when using our super-resolution image transformation framework, an existing trained model could be used, although this might not produce ideal results in all cases.

Strategy to avoid overfitting

To address the challenge of a model performing well on the training set but struggling to generalize effectively to cross-validation or unseen data, several strategies were implemented to enhance the model’s adaptability while avoiding overfitting. The primary approach involves data augmentation, which increases the diversity of the training dataset, thereby improving the model’s ability to generalize to unknown samples. Specifically, the original images are augmented by flipping them horizontally and vertically, followed by rotations of 30°, 45°, 60°, and 90°. Additionally, the images are scaled to various sizes, further enriching the dataset and helping the model learn more robust features across different spatial scales.

To complement data augmentation, regularization techniques such as dropout are integrated into the network design. Dropout is applied during the training process to mitigate the risk of overfitting by reducing the co-adaptation of neurons. By randomly deactivating a subset of neural nodes during training, dropout forces the network to become less reliant on specific features, thereby improving its robustness and preventing the model from becoming overly dependent on local patterns. This is particularly important in scenarios where the dataset is limited in size and diversity, as it helps the model maintain generalization across different samples.

Furthermore, the design of the model itself plays a critical role in enhancing generalizability. Our approach utilizes a CycleGAN architecture with multiple residual blocks, which not only streamlines feature extraction but also supports the model in capturing complex patterns within small datasets. The residual connections help mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, enabling the model to converge more effectively while retaining important details. This design choice is especially beneficial in small-data scenarios, as it allows the model to extract and preserve meaningful features that generalize well to diverse sample types. Super-resolution model robustness validation tests, as shown in Fig. S5, further demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach. Additionally, different generator network configurations, such as the number of residual blocks and dropout settings, have been explored, which influence the results, as shown in Fig. S6.

Strategies to prevent artifact generation

The data augmentation techniques discussed above also play a crucial role in reducing artifacts, as they help the model learn more robust mapping relationships between image pairs. By training the model on a diverse set of augmented images, the likelihood of generating artifacts during inference is minimized. However, noise in the optical super-resolution images can still pose challenges for accurate image-to-image mapping. To address this, noise reduction is performed, and image edges and contrast are enhanced during the pre-processing phase to ensure that the input data is of high quality. These steps are vital for producing sharper and clearer SEM images.

In addition to pre-processing, the design of the GAN model, which is based on a deep residual network, contributes significantly to artifact suppression. The model leverages multiple residual blocks, skip connections, and block regularization to produce stable and high-quality outputs. The generator network focuses on creating noise-free images, while the discriminator network, trained on these enhanced images, becomes adept at distinguishing real from generated images. This dual approach not only improves image fidelity but also effectively suppresses the formation of artifacts.

To further validate the spatial consistency of the generated images and assess residual discrepancies, we conducted a spatial error analysis of super-resolution reconstruction via pixel-wise difference mapping, as shown in Fig. S7. This analysis reveals that the most significant reconstruction errors occur near sharp edges and high-frequency regions, providing valuable insights into potential sources of visual artifacts.

Given that the image pairings in this study are manually aligned, alignment errors could introduce inaccuracies. As such, our loss function does not include traditional image evaluation metrics like PSNR or EPI, which are sensitive to global alignment issues. Instead, a specialized loss function from ref. 30 is adopted, which is better suited for handling misalignments in image-to-image translation. For future work, if precise alignment can be achieved, incorporating PSNR or EPI as part of the loss function could further enhance the quality of the super-resolution results by guiding the network toward more accurate reconstructions.

link